Why Los Angeles School Workers Are on Strike

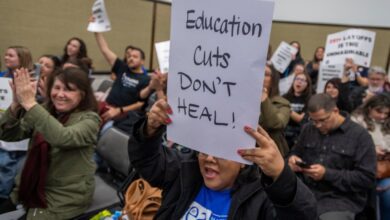

LOS ANGELES — Tens of thousands of Los Angeles school employees continued to strike on Thursday, forcing hundreds of campuses to remain closed and canceling classes for 422,000 students.

The strike began Tuesday at a bus yard in the San Fernando Valley, north of downtown Los Angeles, and was scheduled to last for three days. Classes are expected to resume on Friday across Los Angeles Unified, the second-largest school district in the nation.

The union, which represents 30,000 support workers in the school district, is seeking a 30 percent pay increase, saying that many employees make little more than the minimum wage and struggle to afford the cost of living in Southern California.

The Los Angeles teachers’ union asked its 35,000 members to walk out in solidarity and to avoid crossing the support workers’ picket lines.

Parents scrambled this week to make child-care arrangements because the walkout by both the support workers and the teachers necessitated shutting down more than 1,000 schools. Some students stayed with relatives, others went to recreation centers and some even joined their parents at work.

The strike rekindled frustrations that parents felt during the lengthy school closures prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic. But many parents in the district also have expressed support for the school workers.

Here’s what we know about the walkout.

Who is on strike?

The dispute involves Local 99 of the Service Employees International Union, which represents people who work for Los Angeles Unified in a variety of nonteaching jobs, like bus drivers, cafeteria workers, special education assistants and gardeners. The union announced on Monday afternoon that its members would strike for three days, on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday.

United Teachers Los Angeles, which represents teachers and some other district employees, is not a party to the labor dispute but said its members would not cross Local 99’s picket lines.

The work stoppage is the first joint walkout by the district’s two largest unions, according to Alberto Carvalho, who became the superintendent of the district just over one year ago.

Why is the strike only for three days?

Local 99 said that it was calling for a limited strike this week specifically to protest unfair negotiating tactics by the school district, rather than calling a general walkout over work conditions and pay. Under the law, the union said, this type of strike comes with protections for workers who walk out, but it must have a set time limit and cannot be open-ended.

Los Angeles Unified asked the state last week to block the planned strike, arguing that the union was actually protesting over pay, not negotiating tactics, and that it had not exhausted all of the bargaining steps required before striking over economic issues. A state board said over the weekend that it would not impose an injunction against the strike.

So far, Karen Bass, the new mayor of Los Angeles, and Gov. Gavin Newsom of California, both Democrats, have kept a low profile in the dispute. Unlike in some cities, the Los Angeles mayor does not control the school district, which is run by an independently elected board.

Ms. Bass has been “deeply involved” in negotiations but has tried to work behind the scenes, she said in an interview on Tuesday. Local 99 said on Wednesday that the mayor was hosting the union’s discussions with the district.

Mr. Newsom has discussed the strike with Ms. Bass and is receiving updates from the union and the district, said Anthony York, a spokesman for Mr. Newsom. But the governor had no immediate plans to become involved in the negotiations, Mr. York said.

What are the workers seeking?

Contract negotiations between Local 99 and Los Angeles Unified began in April 2022, and Local 99 declared in December that the talks were at an impasse, according to the union. Its members voted overwhelmingly in February to authorize a strike.

Its members “know a strike will be a sacrifice, but the school district has pushed workers to take this action,” Max Arias, the executive director of Local 99, said in a statement.

The union is seeking a 30 percent overall raise; an additional $2-an-hour increase for the lowest-paid workers; and other increases in compensation. Local 99 said its workers made an average income of $25,000 a year.

Many of the union’s members work part time for the district; the full-time equivalent average was not available. A union chart showed that after-school workers, campus aides and cafeteria employees were the lowest paid members.

A counterproposal from the district, announced by Mr. Carvalho, the superintendent, at a news conference late on Monday, included a 23 percent recurring increase and a 3 percent cash-in-hand bonus.

The union, Mr. Arias said, is steadfast in its demands. “They’ve ignored us,” he said of the district, in an interview on Monday.

The teachers’ union is also in contract discussions with the district but has not called its own walkout, other than saying it will honor Local 99’s picket lines this week. The district’s latest proposal for teachers includes a 5 percent increase for this school year, a 6 percent raise next year and a 3 percent increase in the 2024-25 school year. In October 2022, the teachers’ union called for a 20 percent pay increase.

What might happen next?

So far, there has been no indication that the union and school district will reach a deal this week. The limited duration of the strike has resulted in a lower sense of urgency because classes are scheduled to resume on Friday.

Local 99 could call another strike in the future if union leaders believe contract talks are stalled.

The dispute has coincided with the annual spring window for school district budgeting in California. School districts typically wait for the governor to update the state’s revenue projections in May before making serious budget decisions. Besides passing spending plans for the next fiscal year that starts July 1, school districts need to ensure that they can balance their budgets for two subsequent years.

How common are education strikes?

In 2019, the teachers’ union in Los Angeles Unified went on strike for the first time in 30 years. School campuses stayed open, but student attendance was low.

Eric Garcetti, a Democrat who was mayor of Los Angeles at the time, stepped in to help broker a deal to end the walkout.

Later that year, teachers went on strike for a week in Oakland and for a day in Sacramento. Teachers and staff members walked out in Sacramento in 2022, reaching a deal with administrators on pay raises and benefits after eight days.

In the fall, 48,000 unionized University of California employees, most of them graduate students, walked off the job for nearly six weeks. They secured significant increases in starting salaries, higher pay scales for experienced workers and extra compensation for those who work in particularly expensive California cities.

Strikes, especially by teachers and education workers, have become increasingly common over the past six years, a reflection of widespread employee frustration with low wages, poor working conditions and growing income inequality, according to Kent Wong, director of the U.C.L.A. Labor Center. Public support for organized labor is at a 50-year high in the United States.

Moreover, the nation has recently been experiencing its highest inflation rates since the 1980s. And education workers have seen some private-sector employees successfully negotiate for more pay as employers struggle to hire and retain qualified staff.

“There’s tremendous discontent among working people that this isn’t working for them,” Mr. Wong said. “The rise in worker organizing and the rise in worker strikes is absolutely a sign of the times.”

The job market remains tight, giving leverage to workers, but unions may feel their window to press for higher pay is closing, as recession concerns are on the rise.

What are students doing while schools are closed?

Some schools are providing supervision, without class instruction, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. during the strike. Eighteen recreation centers in Los Angeles County are offering free games, open gyms and computer labs for children to use from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. during the school work stoppage.

The Los Angeles Zoo has offered free admission to students and $5 tickets for adult chaperones during the strike.

Besides supervision for children, a major concern is ensuring that children are properly fed. When schools are in session, the district offers free breakfast and lunch for all students, regardless of income, and many children rely on those meals. Most students enrolled in the Los Angeles district come from low-income households.

The district provided six grab-and-go meals for each student on Tuesday from specific food distribution sites — intended to cover breakfast and lunch for three days.

While out of classes, students have access to instructional material and on-demand tutoring.

Shawn Hubler contributed reporting from Sacramento.