Southern California’s water chief pushes for transformation

When Adel Hagekhalil speaks about the future of water in Southern California, he often starts by mentioning the three conduits the region depends on to bring water from hundreds of miles away: the Los Angeles Aqueduct, the Colorado River Aqueduct and the California Aqueduct.

As general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, Hagekhalil is responsible for ensuring water for 19 million people, leading the nation’s largest wholesale supplier of drinking water. He says that with climate change upending the water cycle, the three existing aqueducts will no longer be sufficient.

Southern California urgently needs to buttress its water resources, he says, by designing the equivalent of a “fourth aqueduct” — not another concrete artery to draw water from distant sources, but a set of projects that will harness local water supplies and help prepare for more intense extremes as temperatures continue to rise.

“The organization is going through a transformation,” Hagekhalil told employees during a recent visit to a water treatment plant. “It’s all about us adapting,” he said, and the water district must prepare for hotter and drier times as global warming continues to undermine the region’s water lifelines in the coming decades.

For Southern California to adapt, Hagekhalil said, it will need to recycle more wastewater, capture stormwater, clean up contaminated groundwater, and design new infrastructure to more nimbly transport and store water, taking advantage of wet years such as this one to prepare for longer and more severe droughts.

Whether he is ultimately able to deliver on these ambitious goals could be determined in part by the actions of the board that hired him. The MWD’s 38-member board has a history of contentious politics, and resistance to change among some leaders might slow Hagekhalil’s efforts to revamp priorities at the district, where he oversees more than 1,900 employees and more than $2.2 billion in annual spending.

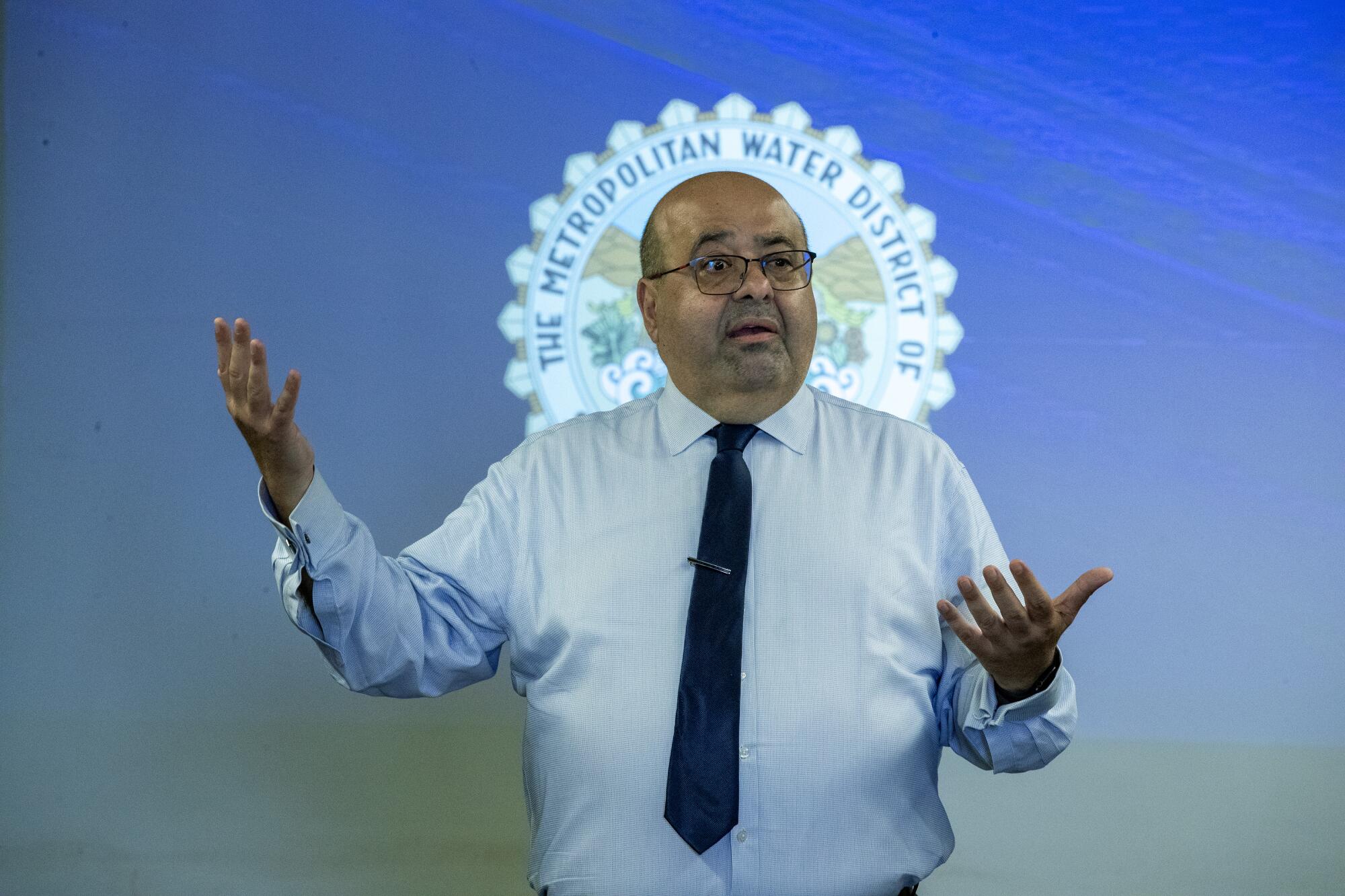

Adel Hagekhalil, general manager of the MWD, speaks at Weymouth Water Treatment Plant in La Verne.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

But Hagekhalil, who previously managed sewer systems and street services for Los Angeles, has a reputation for being an affable, diplomatic manager who isn’t afraid to take on difficult tasks and values hearing from all sides. He has made headway building alliances to advance his goals. And he also has a disarming demeanor, with a playful streak and a knack for using slogans to market his priorities.

He took the job in 2021 after a bitter debate among board members, some of whom said they saw him as too inexperienced in Western state water politics. After the board narrowly voted to hire him, Hagekhalil sought to emphasize unity, and began wearing a blue lapel pin with the slogan “We Are One.”

He regularly hands out the pins to board members, employees and others.

“I’m a believer in branding,” Hagekhalil said. “And I believe that I probably am pretty good at doing it.”

Tracy Quinn, an MWD board member and chief executive of the environmental group Heal the Bay, said she thinks Hagekhalil is succeeding in bringing people together around a vision of holistic water solutions.

“Adel is a convener,” Quinn said. “It’s been really impressive to watch him do what he’s known for: building a bigger tent, bringing people in, getting buy-in.”

Hagekhalil earns $465,000 a year as general manager. The 58-year-old engineer regularly talks with top state leaders and members of Congress. He has built rapport with environmental activists by joining them in virtual meetings to hear their concerns about the climate crisis, conservation efforts and proposed infrastructure projects.

Hagekhalil’s openness to listening is a welcome change and a sign that he is trying to take the MWD in a new direction, says Charming Evelyn, who chairs the Sierra Club’s water committee in Southern California.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Hagekhalil, who has a reputation for being an affable, diplomatic manager. greets employees during a safety fair at the Diemer Water Treatment Plant in Yorba Linda.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

His openness to listening is a welcome change and a sign that he is trying to take the agency in a new direction, said Charming Evelyn, who chairs the Sierra Club’s water committee in Southern California. She said she sees him as a “people pleaser,” who knows what each camp wants to hear and is careful not to antagonize anyone while trying to strike a balance.

“He is walking a tightrope,” Evelyn said, “trying to please the folks that have been there a very, very long time, that don’t like change, and trying to see how he can implement change in increments.”

She said she expects Hagekhalil’s campaign will be a difficult test, a “rough road.”

Hagekhalil is optimistic.

“I think it’s a great opportunity to really reshape the future and build the infrastructure for the next hundred years,” he said. “Time is not on our side. We cannot act with anything less than urgency.”

Hagekhalil said California’s current water challenges demand ambitious innovations on the scale of the works planned more than a century ago by William Mulholland, who led L.A.’s water department and oversaw the construction of the aqueduct that took water from the Eastern Sierra and enabled the rise of Los Angeles. Now, he said, Southern California needs a new “Mulholland moment,” but one based on a new ethic of developing solutions to withstand climate change.

Adel Hagekhalil says Southern California needs a new “Mulholland moment,” but one based on a new ethic of developing solutions to withstand climate change.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

:::

On a recent morning, Hagekhalil met with workers at the Robert B. Diemer Water Treatment Plant in Yorba Linda, where he spoke about the importance of workplace safety and the changes he is prioritizing. He talked about the climate adaptation plan the district is preparing to become more resilient and more self-reliant on local sources.

“What we did the last hundred years was great, but we know that the Colorado River is drying up,” Hagekhalil said. “The future is ensuring that everyone has safe, reliable water across the region, with no one left behind.”

After taking questions, Hagekhalil handed out raffle prizes, including water bottles and earbuds.

Then an employee drove him to the MWD headquarters in downtown Los Angeles. Walking into his office, he passed a wall with rows of black-and-white portraits of the 13 other men who have led the agency since its founding in 1928, followed by a color photo of Hagekhalil smiling.

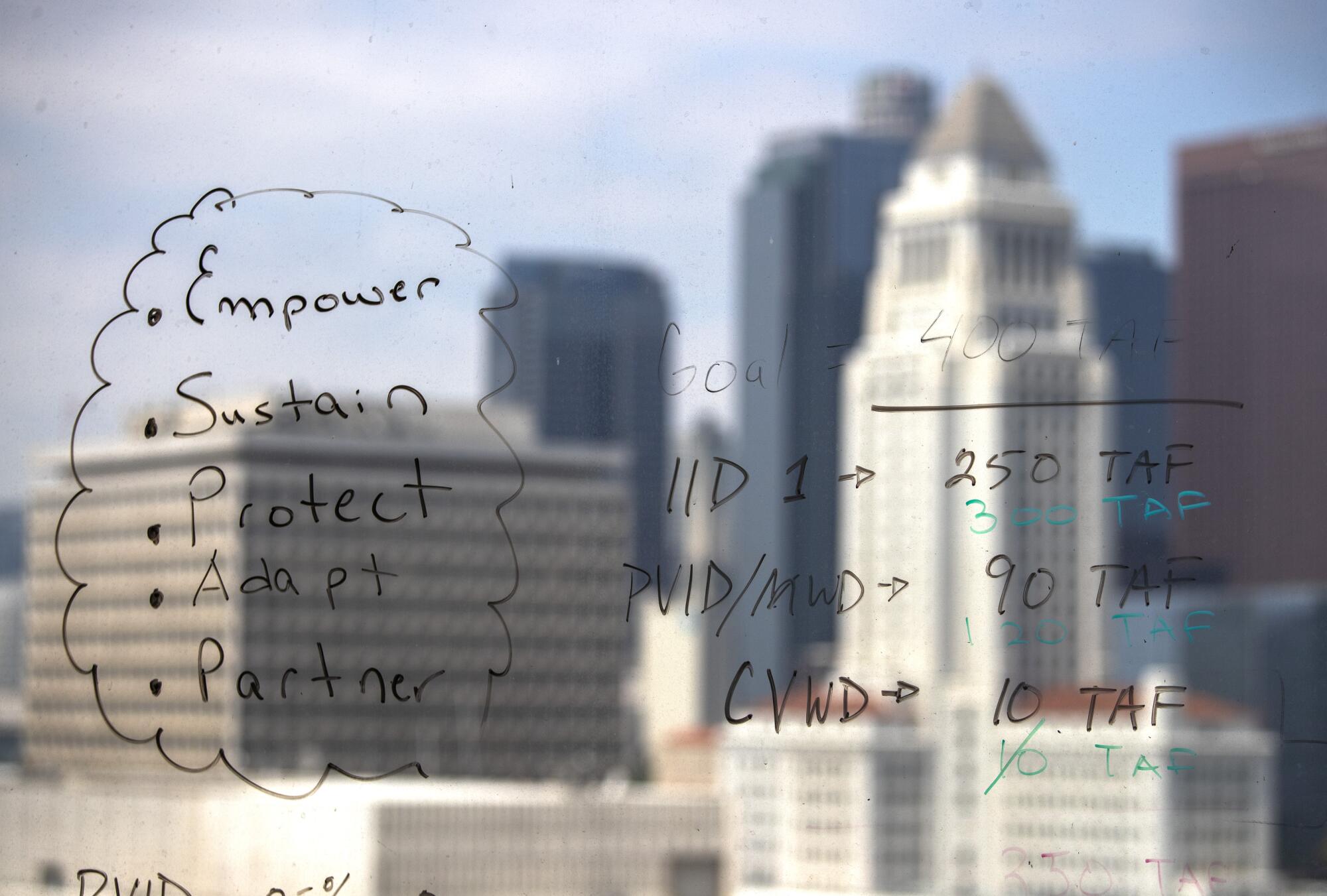

He has used his office window, which overlooks the 101 Freeway, as a whiteboard of sorts, with a list of five bulleted words written in black marker on the glass: Empower. Sustain. Protect. Adapt. Partner.

Hagekhalil said he distilled his goals into these five categories, which he calls “anchors” to guide the organization.

Adel Hagekhalil has written his five “strategic priorities” in marker on his office window overlooking downtown Los Angeles.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

In a series of meetings with managers, Hagekhalil discussed a project in the Antelope Valley that will store water underground, efforts to work with partner agencies to bank water elsewhere, and the district’s plans to rework its system to provide redundancy in areas that now rely solely on imported water from Northern California via the State Water Project.

He chatted by phone with Assemblymember Laura Friedman (D-Glendale) about a bill the district is supporting to prohibit the use of drinking water for grass that is purely decorative along roads and outside businesses.

Hagekhalil received an update on a planned project in Carson called Pure Water Southern California, which is slated to become the country’s largest wastewater recycling facility, at a cost of $5 billion to $7 billion. It’s scheduled to deliver its first water as soon as 2028, and later reach full capacity in 2032, treating 150 million gallons a day, enough to supply about half a million homes.

That recycled water is intended to help offset declines in supplies from the shrinking Colorado River — a goal that agencies in Nevada and Arizona have supported by contributing money for the planning work.

Hagekhalil said he expects the share of water that Southern California gets from imported sources, now about 50%, to shrink in the coming decades to roughly 30%. He said that will be driven by expected long-term declines in available supplies from the Colorado River and the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, a gap that will need to be filled with other supplies.

The district also must prepare for more of the heat-supercharged “climate whiplash” conditions that California has been experiencing, he said, including the driest three-year period on record from 2020-2022, followed by one of the wettest winters in decades.

Even with the state’s reservoirs now nearly full, Hagekhalil said it’s crucial not to lose momentum on building infrastructure projects such as the water recycling facility, because the state could soon be dealing with even more severe bouts of dryness.

Last year, the drought situation was so dire that the district imposed mandatory water restrictions in areas that depend on the State Water Project, affecting nearly 7 million people and leading to a dramatic reduction in water use. Hagekhalil said the shortages could have worsened if the drought had persisted, and he intends to prevent a repeat of — or any scenarios like — the crisis of 2017-18 in Cape Town, South Africa, when residents lined up to fill jugs as declining reservoirs approached a feared “Day Zero.”

“I don’t want people ever to be in a place where they do not have water,” Hagekhalil said. “This cannot happen here.”

Hagekhalil’s values and views were partly shaped by his experiences growing up during the civil war in Lebanon, where his Palestinian family lived through bloodshed, hardships and water shortages. For a time in 1982, after Israeli troops invaded, they had no running water at home, so Hagekhalil would line up to fill two jugs at a communal spigot.

“When that water came out and you filled your jugs, you’re coming home, you’d have a big smile,” Hagekhalil said. “I know what the value of water is.”

Later, as fighting raged between the Lebanese military and militia fighters in 1984, his family was living in a second-story apartment when a rocket hit, ripping through the home and exploding on the floor below, killing many neighbors. Hagekhalil, who was then 19, said he remembers his mother had him lie in a bathtub and covered him so he wouldn’t be wounded.

When the family fled to an underground shelter, Hagekhalil carried his grandmother, who was ill. He also carried two suitcases and remembers stepping past dead bodies as he fled.

After a stint living in a hotel, Hagekhalil and his parents took a cab to Syria and boarded a flight out of the country. They moved to Houston, where Hagekhalil’s older brother was living, and embraced their new home.

“Deep inside, when you go through this trauma, it stays with you. And that’s why I don’t like to see people who are traumatized,” Hagekhalil said. “I want to help people.”

He said he isn’t particularly religious, but he follows the teachings of Islam in seeking to care for others. Early in life, Hagekhalil wanted to become a doctor to help save lives. Even though he ended up studying engineering, he said he sees his current work of ensuring people have clean water as being, in a way, about saving lives.

“To me, I’m the top surgeon now,” he said with a chuckle. “So it starts from my dream of being a doctor, to now probably being a water doctor.”

Continuing with the analogy, he said he’s working to “help heal this patient that we’re dealing with because of climate change, to make it continue for the future and live long.”

Doing that requires shifting the agency’s focus from being purely a water importer to being more of a regional steward and caretaker of water, he said, “a co-op to build this reliability system for everyone.” He said the transformation also requires changing the financial model from one that depends on selling imported water to member agencies, to one that will support investments in local infrastructure.

“ ‘How are we going to pay for it’ is going to be the biggest discussion that the board should take on,” he said.

While the agency’s former leaders helped spearhead a controversial state proposal to build a water tunnel in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, Hagekhalil has taken a different approach, saying he hopes to see more analysis of the long-term water-supply benefits that the project would bring.

“We can’t put all our eggs in that one basket. In the past, everyone was focused on the delta as the solution for our future,” he said. “We need to diversify. We need to look at other options.”

Hagekhalil takes in a view of the lobby at MWD headquarters. He says he’s working to “help heal this patient that we’re dealing with because of climate change.”

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

At the same time, Hagekhalil sees one of his key tasks as addressing the organization’s internal woes, including issues of discrimination and harassment of women, which last year led to a scathing state audit showing the district failed to commit resources to properly investigate complaints of misconduct, among other failings. Hagekhalil tells his managers they are crucial in “creating this culture of inclusion.”

This isn’t the first time Hagekhalil has campaigned for change. In his previous work for the city of L.A., he led various efforts, including reducing sewer spills and experimenting with efforts to cool streets by painting pavement a light shade to reflect sunlight.

At times, he showed his playful side. In the early 2000s, when the city launched a campaign urging restaurants to stop dumping grease into sewers, Hagekhalil dressed up as a superhero called the Grease Avenger, appearing at community events wearing a blue leotard, mask and purple cape. He said the gimmick worked, helping to raise awareness.

Now, his goals are bigger and his responsibilities are weighty. But he said he’s simply building on an approach he has always taken in his work: never saying no to a difficult task.

He said his style as a manager draws on a bit of wisdom he gleaned years ago from the title of a book about stress and spirituality by Brian Luke Seaward: “Stand Like Mountain, Flow Like Water.”

Hagekhalil said he thinks about being strong to face challenges but being “flexible, adaptable and welcoming like water.”

“You can move around the challenges you’re facing, and not be stopped in that effort,” he said.