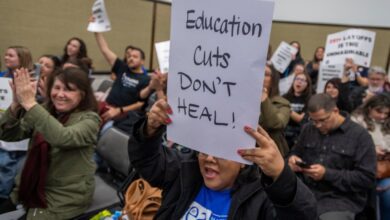

Opinion: The achievement gap in Southern California’s education system

This inaccessibility due to expenses is one example of the achievement gap. In schools, the achievement gap is a difference in academic performance between groups of students. It arises at a young age, when students are born into a particular social class, race, disability, or gender.

Although these factors shouldn’t hinder students, they can create barriers like unequal learning advantages, which prevents students from scoring as high as more privileged students on standardized tests.

In Anaheim, a field trip showed Superintendent Matsuda the persistence of poverty among his students. While taking his students out on a field trip to a World War II US-Japanese internment camp, one student remarked how the camps had better housing conditions than his own home.

After hearing this, Matsuda reported the incident to his administrators, asking, “How far have we come? Which is not very far, right? If our kids are sleeping in worse conditions than the concentration camp.” In Anaheim, if a student could barely afford housing, how would they be able to buy school materials?

This begs the question: Can schools and students successfully bridge the achievement gap, and how should it be approached?

Looking at funding in Orange County, we can see a correlation between local versus state funding and the test scores in school districts. According to US News, an average of 68.45% of education is funded by locals in Irvine; in the Newport-Mesa district, 80.9% of education funding is provided by locals.

In cities like Anaheim, Santa Ana, and Garden Grove, the majority of funding is provided by the state at an average of 62 percent rather than coming from locals.

Comparing the test scores between these different cities statistics according to US News, it’s clear that funding matters. Cities relying mainly on local funding show increased test scores compared to state-funded cities.

Money’s impact on the achievement gap also occurs internationally, in England. In 2020, disadvantaged students aged 16-19 were as many as three grades behind, according to David Robinson, co-author of the EPI report.

Less funding leads to less resources, help outside of school, and less overall academic achievement. According to Bruce D. Baker, increased funding leads to a higher quality of education, more access to extracurriculars and professional help or tutoring. Both sources show how money is the main barrier between achievement gaps and academic performance.

As the Shanker Institute reports, money does matter, “On balance, in direct tests of the relationship between financial resources and student outcomes, money matters.”

However, simply providing more money is only sometimes the answer.

One of the report’s co-authors, Emily Hunt, EPI Associate Director, told the Nuffield Foundation in 2022, “the government must do more to address the fundamental drivers of deep-rooted educational inequalities, including poverty.”

Addressing poverty to bridge the achievement gap is a complicated issue. A more equitable allocation of financial inputs could provide a better underlying condition to improve academic achievement.

Academic achievement and social inequality are important issues to address because they impact a nation’s longevity. In 2015, electoral candidate Bernie Sanders tweeted how nations cannot survive morally or economically with huge social gaps.

In California, the State Board of Education has proposed several solutions this year. In May 2023, the board approved $750.5 million in grants for community schools, which help by providing “students, and their families, the resources and support they need to thrive – including counseling, nutrition programs, tutoring, social services, and health care and mental health care services.”

In February, Governor Gavin Newsom also proposed the new K-12 Omnibus Trailer Bill, which “explicitly calls for addressing disparities among racial groups, with the expectation that districts would use extra funding intended for underperforming students.”

In conclusion, simply throwing money at lower-performing schools and students is not the answer. Addressing poverty in communities and schools is a complex issue, one that requires providing more community services, not just money.

Walking across schools in Irvine, I always notice how fortunate I am to be in the Irvine School District. As someone who is privileged, I can’t help but wonder what I can do to keep awareness of my peers in the cities around me. Despite its many flaws, like its competitive environment, I believe that going to the Irvine School District has made a difference in my education. I believe that social inequality should be taught at schools so that future generations can learn how to make a difference in education.