Louisiana student’s death reminds why hazing is hard to stop | Education

The criminal case forming against three suspects in last month’s fraternity hazing death of Southern University junior engineering student Caleb Wilson is one of Louisiana’s first uses of its felony anti-hazing law called the Max Gruver Act.

The state Legislature passed the act in 2018 and named it after the LSU Phi Delta Theta fraternity pledge, who died from alcohol poisoning in a hazing incident in 2017. It allows prosecutors to bring a felony charge in hazing incidents of coerced consumption of alcohol, serious bodily harm or death.

Former Southern student Caleb McCray, 23, Kyle Thurman, 25, an Omega Psi Phi fraternity member, and Isaiah Smith, 28, a Southern graduate student entitled “dean of pledges” for the university’s Omega Psi chapter, were arrested and booked by authorities on felony hazing counts tied to Wilson’s Feb. 27 death. McCray also faces a manslaughter charge.

The Omega Psi pledging ritual that took place in a Baton Rouge warehouse claimed the life of the 20-year-old Kenner native, authorities said.

East Baton Rouge Parish District Attorney Hillar Moore said he’ll take this fraternity hazing case that’s made national headlines to a grand jury to finalize criminal charges against the alleged perpetrators.

Family and friends hold a second line after the Celebration of Life Services for Caleb Wilson at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Kenner, La., Saturday, March 15, 2025. (Photo by Sophia Germer, The Times-Picayune)

Outside the legal arena, Wilson’s tragic death started a familiar saddening conversation in Baton Rouge and across Louisiana: How can deadly fraternity hazing rituals finally be stopped — for good?

Southern University Board Chair Tony Clayton, the district attorney in West Baton Rouge for Louisiana’s 18th judicial district, said one solution is to take fraternity recruitment out of the hands of undergraduate students.

“I’m going to propose that the graduate chapters, in regards to Southern, are to be in charge of intake, as opposed to having undergrad kids do the intake or initiation,” Clayton, who earned a law degree from Southern, said in an interview.

Tony Clayton, district attorney for the 18th Judicial District, heads to his seat before first pitch between LSU and Southern, Tuesday, February 18, 2025, at Alex Box Stadium on the campus of LSU in Baton Rouge, La.

“If the kids are going to want to become a member of the fraternity or sorority, the initiation would have to go through the graduate chapters, which are professional men and women.”

Clayton plans to campaign around the state, visiting graduate chapters of the Divine Nine, the nation’s nine historically Black college fraternities and sororities. He also plans to submit a change to Southern’s bylaws.

‘Be honest about it’

Ted James, a former Baton Rouge state representative for Louisiana’s 101st District, supported the passage of the Max Gruver Act while serving in the state House.

When news broke of Wilson’s death, James said he could tell from the first reports it was going to be related to hazing.

James, 43, holds Southern University undergraduate and law degrees and belongs to a Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity graduate chapter. As a graduate member of the Divine Nine and a community leader, James said he and other fraternity brothers can’t be silent about hazing present in their organizations’ cultures and their own frat experiences.

“Twenty-four years ago, did I ever think that I was in a position that I was not going to survive? Absolutely not,” James said.

“Did I, quite honestly — and I think that it’s important for me and others to be honest about it — did I do some things that I probably shouldn’t have done? Absolutely.”

Lifelong commitment

The respect Black Greek organizations command among potential recruits also comes from the history of leadership Divine Nine graduates have in the Black community. Membership isn’t an undergraduate commitment, but a lifelong one, in which graduate members conduct charity and service and pay dues to their organizations.

Vanessa LaFleur, D-Baton Rouge, the District 101 state representative, said she thought of her own children when she heard about Wilson’s death.

“My initial reaction was just deep sorrow,” she said. “When I see his face, I see my son’s face, who as a college student I have no doubt wants to pledge a fraternity one day.”

LaFleur, also a Southern University graduate, is a graduate adviser at Southern and a Alpha Kappa Alpha member. In her work with students, LaFleur explains to them that as much fun as Greek life is, it carries penalties for those not following the rules.

Rep. Vanessa Caston LaFleur, D-Baton Rouge, speaks on the House floor during a special legislative session, Tuesday, November 12, 2024, at the Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge, La.

“My daughter just went through the process in 2024 at Southern, in my old chapter,” LaFleur said. “I was very proud of that process, because it was by the book, every bit of it, because the graduate chapter was in charge of the process.”

James said it frustrates him when blame is aimed toward Southern University, when the hazing ritual authorities said caused Wilson’s death was off-campus.

“There’s no way for Southern to be responsible for thousands of students when they leave campus,” he said.

Clayton and James both emphasized that unlike Max Gruver’s fatal hazing incident, the pledging ritual leading to Caleb Wilson’s death took place off Southern’s Baton Rouge campus.

Southern officials require all National Pan-Hellenic Council organizations, including Omega Psi Phi, to put new members through an anti-hazing training as part of their admissions process.

Council organizations are also required to have a specific anti-hazing statement. Omega Psi’s “zero tolerance” hazing policy statement prohibits both “physical shock” and after-hours activities during its intake activities.

“So there are a lot of efforts put on educating young people about what not to do. And, you know, there are folks that have just made some horrible, horrible decisions,” James said.

Ted James answers a question during the mayoral debate at Manship Theatre on Wednesday, October 2, 2024.

Southern University is conducting an internal investigation into the circumstances of Wilson’s death.

Meanwhile, university President Dennis Shields said Omega Psi Phi was ordered to “cease all activities” at the university. Additionally, the university suspended all campus club and Greek life recruiting through the academic year, he said.

Hazing history

Hazing has been part of American university culture since the 1850s, said Walter Kimbrough, a former president of Dillard University and a hazing-crime expert witness.

At that time, hazing was undertaken by upperclassmen against freshmen.

“Hazing was pretty ubiquitous in American higher education by the 1920s,” Kimbrough said. “But that’s when colleges and universities stopped allowing the hazing of freshmen. So you had this culture that had been on campuses for 70 years, and people where trying to figure out where does it go?”

Fraternities and sororities, as private organizations, became the outlet for these impulses.

Black Greek-letter organizations, formed by the earliest Black collegians to foster community between each other and incubate future leaders, didn’t yet induct “pledges” at that time.

Kappa Alpha Psi, a historically African-American fraternity, was founded in 1911, but didn’t have any formalized pledge activities until 1919, which coincides with the time “when colleges and universities around the country said there’s no more hazing of freshmen,” Kimbrough said.

The Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, the oldest collegiate Black fraternity, started in 1906, and its first pledge class was in 1921.

Pledging in the Divine Nine organizations officially ended about 70 years later, after the hazing death of Joel Harris in 1989 at Morehouse College in Atlanta while pledging for Alpha Phi Alpha.

At that time, presidents of eight Black Greek-letter organizations came together to officially end pledging initiation. They replaced it with an admissions process disallowing hazing, Kimbrough said.

Then, the same way the hazing culture shifted from the general student body to only Greek organizations in the 1920s, it again shifted, continuing underground and out of sight.

A group of mourners gather in a prayer circle during the memorial of Caleb Wilson at Southern University’s F.G. Clark Activity Center on Friday, March 14, 2025.

‘Dying to belong’

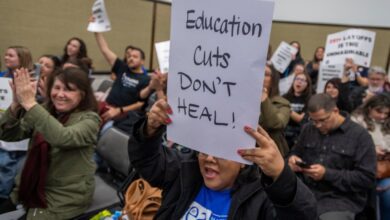

Students face immense social pressure to go along with hazing rituals, despite official warnings they receive about its danger and illegal

Akeya Simeon calls this phenomenon “dying to belong.” She is assistant director of the University of West Virginia’s Center for Fraternal Values and Leadership and a Delta Sigma Theta member.

In Kimbrough’s years of analyzing hazing incidents, he’s noticed those that hold the most sway over undergraduate fraternity members are not the leaders or elders of the organization. Instead, it’s the younger, more-recent graduates.

“That’s part of the challenge, because there is this influence of people who are older, a group I call ‘extended adolescents,'” the former Dillard University president said. “They’re 24 to 30 years old. They have graduated and left. … They’re continuing to live their undergraduate experience, but they have a lot of sway on the chapter.”

To Kimbrough, this group is often overlooked when examining hazing culture within a Greek organization.

“The problem is, these people are invisible to the real leaders of the organization. They aren’t members of graduate chapters. They don’t go to conventions or meetings,” he said.

“… They’re not financially active with the fraternity, but (pledges) listen to them because they pledged there three or four years ago and they respect that.”

Including frat members in policy setting

Another cultural difference between white Greek organizations and the Divine Nine are the methods used in hazing pledging rituals.

“In predominantly white groups, particularly fraternities, the hazing really is more through the alcohol,” Kimbrough said. “Whereas for historically Black groups, I can’t think of a case where there was a death due to alcohol poisoning. It’s always been physical.”

In this way, the deaths of Max Gruver and Caleb Wilson are demonstrative of the kinds of hazing carried out by each organization the young men were pledging to join.

Indeed, Wilson, a former trumpet player for Southern University’s famed Human Jukebox marching band, died as a “direct result” of being punched in the chest while pledging for the Omega Psi fraternity inside a 3412 Woodcrest Drive warehouse, Baton Rouge Police Chief Thomas Morse Jr. said.

During the ritual, pledges were brought to the building and forced to change into gray sweatsuits. With Wilson and eight other hopefuls lined up according to height, McCray and two others took turns punching them in the chest using a pair of black boxing gloves, according to McCray’s arrest warrant affidavit.

Pallbearers walk the casket down stairs to the hearse during the Celebration of Life Services for Caleb Wilson at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Kenner, La., Saturday, March 15, 2025. (Photo by Sophia Germer, The Times-Picayune)

McCray, whose defense attorney said his client is innocent, delivered the final blow before Wilson collapsed to the floor and began having a seizure. Fraternity members did not call 911 after Wilson experienced the medical episode, and waited to bring him to Baton Rouge General-Bluebonnet hospital early the morning of Feb. 27, sources said.

“What eats at me is the beating,” state Rep. LaFleur said. “There isn’t nothing brotherly about putting your hands on me. That’s not going to build a community.”

Simeon, assistant director of the Center for Fraternal Values and Leadership at University of West Virginia, said the most effective cultural shifts she’s seen occur at the colleges she’s worked with have been when students are actively involved in making new policies.

“Rather than becoming the adversaries of these student organizations, of these fraternities and sororities,” we need to have “roundtable conversations,” she said.

However, when these Greek Life groups break policy she thinks they should be banned from campus — forever.

At Southern University, board chair Clayton intends to seek a ban of Omega Psi Phi frat “anywhere from five to 10 years, just to let them know that we have taken this seriously. A kid has lost his life for no reason.”

In 2005, Omega Psi was kicked off Southern’s Baton Rouge campus for three years, after university officials found “overwhelming evidence” a fraternity pledge was severely beaten, The Advocate | The Times-Picayune archives show.