Education saw a lot of changes in the past year, here’s what could be here to stay – Daily News

A year ago, teacher and instructional coach Susan Ferguson left her classroom as the coronavirus pandemic gained momentum in Southern California, not knowing when she or her students would return.

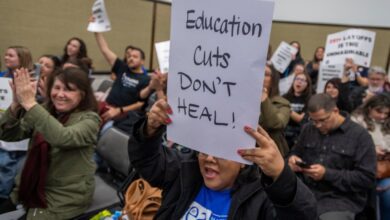

In recent weeks, families across the region have rejoiced with the news some campuses will reopen as the state’s infection rates trend downward, celebrating what they hope is the beginning of the end to home-based distance learning, the challenges it posed and the problems it exposed.

Ferguson, too, looks forward to returning to Thomas Jefferson High School in South Central Los Angeles. But she’s annoyed by comments from distance-learning critics who say the past 12 months have been a waste of time.

“It’s definitely been a challenge,” Ferguson said. “The idea that some people put forth that it’s been a complete failure, I would vehemently disagree with, as someone who has seen my own students learn.”

Now, with schools poised to reopen this spring and into the fall, Ferguson and other educators are looking to the lessons learned during this most unusual academic year and how to improve education for all students moving forward.

‘Made it happen’

One of the most significant bright spots in the past year, many educators and families say, is the intense focus school districts put on technology to try to make virtual learning accessible to all students.

Across the state, districts purchased computing devices and mobile hotspots for students. While the devices haven’t always worked perfectly, and spotty wifi remains an issue for some, distance learning has provided students and teachers more opportunities to pick up 21st century skills.

Corona-Norco Unified School District, for example, had long planned to get a Chromebook for each of its more than 53,000 students.

“Five years ago, what seemed so far-reaching, that it would take years to get devices in the hands of kids, we made it happen in less than a year,” said Lisa Simon, Corona-Norco deputy superintendent of educational services.

For educators who may have been slow to embrace technology in their classroom, many now see the benefits, such as being able to give and get feedback from students more easily.

Access to technology is one thing, however, and managing a child’s education from home is another.

When it became clear the 2020-21 school year would begin with students learning remotely, Nicole Klink created the Hemet San Jacinto Distance Learning Support Facebook group. Now more than 1,300 members strong, the group shares tips on how to make virtual learning work for families, shares information about local school districts’ plans and serves as a place to vent a little.

“Everyone’s trying to do the best that they can, but they don’t feel like they have enough support,” said Klink, a Hemet mother of first- and ninth-graders and an instructional aide for San Jacinto Unified.

The pandemic and abrupt shift to virtual learning laid bare plenty of inefficiencies and inadequacies in current educational models, said Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a professor of education, psychology and neuroscience at the USC Rossier School of Education. But that means educators can now build something better for students.

“This is an opportunity, if we take it, to courageously rethink what school means,” she said. “Rather than regress into those patterns that feel restrictive, but also comfortable because they’re familiar, we need to take this opportunity to examine those structures and reinvent those systems.”

Keeping options open

Though more and more school districts are ramping up to welcome students back, administrators know some families will choose to keep their children home for now — and perhaps well into the future. For all those who say home-based school has been pure misery, there are some for whom it has worked quite well.

Before the pandemic, Taylor Jackson, an 11th grader at a private school in San Fernando Valley, would go to soccer practice right after school and not return home until 10 p.m. Since switching to online schooling, her new schedule allows her to finish her homework by 3 p.m., freeing up more time for extracurricular activities and bonding with family.

“Online school has just helped me so much with my stress,” Jackson said. “Going back at the end of my junior year would increase my stress.”

Katherine Gaudet, 13, an eighth grader at Robert Frost Middle School in Granada Hills, is a straight-A student. She finds there are fewer distractions learning from home and less busywork.

“It’s just enough to help us retain the information without pushing our brain to the limit,” she said of her homework assignments.

But some classes are best taught in person, like her music class. A hybrid schedule where she could be on campus some days and sing in the same room with her classmates would be ideal, she said.

Because of the positive response from some students and families to distance learning, San Bernardino City Unified School District plans to continue offering it as an option after the pandemic, said Rachel Monárrez, assistant superintendent of Continuous Improvement.

“For some kids, the digital learning environment has been really good,” Monárrez said. “So that’s something we’re going to carry forward — we’re going to have a virtual option for our students.”

In fact, some students have thrived the past year, said Immordino-Yang.

“Kids with anxiety disorders, kids with social anxieties, in particular, kids who don’t feel at home in the spaces at school have really relished this opportunity to be less impacted by crowding,” she said. “But a huge portion of kids have really suffered and have even fallen off the radar.”

Addressing ‘learning loss’

Connecting with students who have disengaged from school will be a struggle as districts try to reestablish relationships and help those who have fallen behind academically, educators say.

In February, new state data showed that 155,000 California students had dropped off the rolls in public schools in the past year. That’s five to seven times larger than the typical drop in recent years in the state, where declining birth rates have chipped away at enrollment.

“I’m seeing, by far, the lowest level of participation in my memory,” said Amy Aydin, who has taught sixth-grade math and science at Almeria Middle School in the Fontana Unified School District for more than a decade.

“I’ve never struggled to get along with kids or to have a rapport with kids,” she said, “but the online environment makes it really, really hard.”

Experts agree that, even with everyone’s best efforts, many students have been set back educationally by the pandemic.

“There is likely to be ‘learning loss’ for kids who have not been able to access their classrooms,” said Julie Slayton, a professor of clinical education at the USC Rossier School of Education. “But many of those were already being profoundly disadvantaged in their regular classrooms.”

Distance learning environment is hardest on special education students, English learners and the poor, all of whom already weren’t getting an equal education before the pandemic, according to Slayton.

Corona-Norco Unified students, as a whole, aren’t doing worse, Simon said. But students who were struggling are struggling even more now.

“We did find that we had students that had more Ds and Fs,” she said. “Not necessarily more students, but the students who had Ds and Fs had more than in the past.”

What districts do about a year of learning loss remains to be seen.

“The system is going to have to adjust,” said Sam Buenrostro, superintendent of Corona-Norco Unified. “We are planning summer school earlier than ever before.”

For the first time in a decade, the district will offer summer school for middle school students, along with a four-week session for elementary students. In the meantime, the district offers before- and after-school programs and Saturday school programs, all meant to help students who are falling behind.

As for next school year, “we’re looking at how we accelerate learning,” Simon said. “We take students from where they are currently and provide the best opportunities and support so they can move forward.”

Changing practices

Meanwhile, educators are looking at what the past year has taught them about their profession.

Getting teachers out of their classrooms meant an end to the silos many worked in. Monárrez believes that, even after the pandemic is over, increased collaboration between teachers will continue.

“Once you get a taste of it and you realize ‘this is a really good use of my time, and it helps me to be a better educator,’ and you like doing it, you no longer have to mandate collaboration,” she said. “That’s just human nature, right?”

Online meetings gave Corona-Norco teachers more instructional time since they didn’t have to travel as much. And it’s benefited parent-teacher conferences as well.

“In the past, we’ve required parents to attend certain meetings and it’s been really hard because they work in L.A. and commute a long way,” Simon said. “We couldn’t do that this year, obviously, and did it online and discovered that attendance increased.”

Ferguson, the teacher from South Central LA, has noticed increased conversations at her school about how the staff can address the social-emotional needs of students and is hopeful the focus on the whole child won’t go away once schools fully reopen.

“Some teachers are getting a better understanding of our children’s struggles,” she said, noting that the increased awareness and empathy can alter how educators decide to deal with students who are absent from class. “We really try, as a school, to veer from (asking) ‘Why aren’t you here?’ to ‘How are you? What’s going on?’ and really be supportive of our kids and find out what their needs are.”

Meanwhile, administrators are evaluating how to create an educational system that offers families and students more options.

“The instruction day for some of our students and teachers doesn’t have to remain in the 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. model,” Jerry Almendarez, superintendent of Santa Ana Unified, wrote in an email. “We need to provide more flexibility not just in our daily schedule, but also how we deliver instruction. Online learning can help us meet both of those needs.”

And there may be changes in how student achievement is assessed.

Almendarez said the Santa Ana district temporarily adjusted its grading scale to make it easier for students with a failing grade to receive a D.

Looking forward, the Los Angeles Unified School District is exploring a “mastery-based learning and grading policy.” If adopted, the new policy would offer students multiple ways to demonstrate mastery of the content and standards they’re expected to learn and move away from basing grades on the number of completed assignments.

“While the pandemic has exerted unimaginable pressure and challenges for our students, families and educators, it also provides a unique opportunity to focus on what matters most in teaching and learning,” said Tanya Ortiz Franklin, LAUSD school board member.

Some, however, are skeptical the education establishment will embrace change.

“There will be some minor at-the-edges changes to education, but by and large, the educational system will resist the important kinds of changes that will be necessary to educate our kids,” Slayton predicted.

In the end, Monárrez said she believes today’s students will thrive.

“Long-term, our children are resilient. I think they will look back on this and say ‘wow, that was something,’” she said. “I think our seniors are going to look back and say ‘I was part of a history that no one else can talk about.’”

Originally Published: