A school board’s focus on CRT stirs backlash in Temecula schools

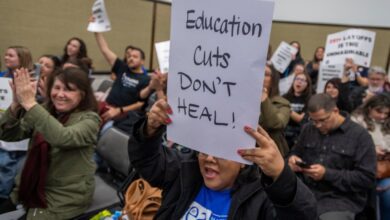

After just six months in office, those officials face a recall effort on top of a civil rights investigation launched by the state’s Democratic-led education department. Students have held protests, and irate parents and teachers are swarming the board’s meetings, feeling that their town — the fast-growing, politically diverse suburb of Temecula in Riverside County — has become consumed by partisan warfare.

“We don’t want culture wars. We don’t want Fox News appearances,” Alex Douvas, a parent of two kids in the district who previously worked for two Republican congressmembers in Orange County, told the board recently. “Our schools are not ideological battlegrounds. They’re not platforms for religious evangelism. These are institutions for learning and growth.”

The religious right saw an opening to jump into the parental rights movement amid intense backlash about pandemic-era school closures and mask mandates. But those policies have all but disappeared in schools, and it’s proving harder to sustain that level of outrage over teachings on race and gender. The effort to ban certain books and challenge curriculum has split Republicans and polled poorly with independent voters nationally.

Local Democrats see the strategy flopping — and are already looking to capitalize on it in a part of the state that has become a battleground for control of the House. Joy Silver, chair of the Riverside County Democrats, said she’s intensely focused on winning down-ballot races like school board seats “because the battles are taking place there.”

In Temecula, the political agenda embraced by school board trustees Joseph Komrosky, Danny Gonzalez and Jen Wiersma has set off a different kind of public outrage than was likely intended. The booing and shouting at a recent public hearing grew so loud that the board president — who appeared to be wearing a bullet-proof vest under his sweater — cleared the room.

“To the extent you keep it focused on parents and students first, not teachers, I think there’s room where you can push back on quote-unquote “woke” agenda issues, but if you go too far in the other direction and are trying to make that the only issue you care about, I think you’re going to see predictable backlash,” California GOP consultant Rob Stutzman said in an interview. “I look at something like Temecula, and to me it’s an eye roll.”

A similar ethos has dominated the campaigns of Republicans like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has made curriculum restrictions and “parental rights” a centerpiece of his bid for the GOP nomination. It could also factor into local and congressional races, particularly in inland California, where Republicans are likely to face strong challenges from the left in 2024.

“I don’t want to say it’s a particularly Republican Party issue, because everyone who is upset by this is not necessarily Democratic, but the people who are causing the trouble are the extremists of that party,” Silver said.

Silver pointed to other parts of California where social policy pushed by the religious right has met organized resistance. A recall attempt is brewing against a conservative majority in Orange County, where a pastor in Chino helped flip the school board. A pastor in San Diego County drew dozens of counter protesters last month after mobilizing his congregation against a proposed school district inclusion policy. So far, the effort is failing to sink the proposal.

An NPR/Ipsos poll conducted in May found that the majority of Americans oppose book bans and curriculum restrictions, with 64 percent saying that school boards should not restrict what students learn. Majorities of GOP respondents also opposed state legislative book bans and content restrictions, the survey found — a cautionary sign for candidates who risk losing centrist voters by leaning too hard into curriculum crackdowns.

Temecula Valley reflects broader changes across inland Southern California. Once agricultural, mostly white and conservative, it has become a fast-growing bedroom community for coastal San Diego and Los Angeles. Along routes that draw tourists for balloon excursions and wine tastings, the former Republican stronghold of Riverside County now is home to more registered Democrats.

But Covid injected a fervor into local politics. Tim Thompson, an evangelical pastor in Riverside County, emerged as an outspoken opponent of mask mandates, along with the California GOP and conservative activist groups such as Moms for Liberty, best known for its anti-vaccine organizing. When churches were ordered closed at the onset of the pandemic, Thompson began railing against stay-at-home orders in sermons and traveled to Sacramento for unsanctioned protests at the state Capitol — one of which led to his arrest.

Thompson waded further into politics in the following months, bringing in Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) to speak at his church when other Southern California venues canceled on her during the summer of 2021. Locally, he pressured the Temecula school board to take up a resolution to disobey a state mask mandate. When they refused, he became irritated.

Barbara Brosch, board president at the time, described a tense period in which elected officials were occasionally escorted home from public meetings by police after being threatened by activists. Brosch — who went to high school with Thompson — said he warned her and other board members that he would run candidates against them if they didn’t go along with his anti-masking proposal.

“Tim asked me to put the resolution on our agenda, or else we would be replaced,” Brosch, an independent voter who describes herself as a conservative Catholic, recalled of a meeting with the pastor.

A year later, Thompson made good on his threat. Three candidates funded by his Inland Empire Family PAC narrowly won in a low-turnout election, defeating Brosch and two other candidates who served on the board during the pandemic.

“This Inland Empire Family PAC was using what sounded like benign language,” said Kristi Rutz-Robbins, a Democrat who served three terms on the school board and now teaches in the district. “I wasn’t even paying attention during the election. It wasn’t in my district, or my trustee zone. And I figured it’d be fine, whoever gets elected.”

None of the board members answered questions from POLITICO at a recent board meeting or responded to multiple inquiries about their decisions or Thompson’s efforts to shape district policy. Kromrosky previously said he does not attend the 412 Church.

But a local GOP leader said he was confident voters would back the officials in a recall.

“The voters in Temecula spoke clearly during the election last November. If the recall qualifies, I have no doubt the voters will speak clearly again,” said Matthew Dobler, chair of the Republican Party of Riverside County. “The Republican Party has faith in voters to decide what’s best for their community.”

On the day they were sworn in, the new board members passed a resolution condemning critical race theory. That landed them on “Fox and Friends” even though the subject wasn’t being taught in Temecula schools. Then they hired an outside consultant to run workshops warning educators about the perils of CRT, a lens used by academics to challenge institutional racism that is viewed by many on the right as simply shorthand for any teaching about race that they don’t like.

But until last month, when a curriculum fight over the late gay-rights leader Harvey Milk got the governor’s attention, many residents hadn’t noticed.

The board rejected a social studies curriculum that featured a half-page biography of Milk, with Komrosky repeating a disputed allegation against the slain San Francisco supervisor. “Why even mention a pedophile?” he said.

State Superintendent Tony Thurmond said people attending the California Democratic Party convention in Los Angeles the following week asked him to get involved. They included delegate Julie Geary, who said she also raised the issue with Attorney General Rob Bonta.

Thurmond, Bonta and Gov. Gavin Newsom already had a joint letter in the works cautioning school districts against banning books and restricting teaching materials for political reasons. But the Democrats, dismayed by the comment about Milk, began to single out Temecula. Newsom called Komrosky’s comment “ignorant” on Twitter. Bonta’s office pressed the district for justification of its decision. And Thurmond traveled back to Southern California to meet with Komrosky and Gonzalez, who had made the same allegation against California’s first openly gay elected official.

“If there was a single factor that was the final push for me to go to Temecula, it was seeing the statement made calling Harvey Milk a pedophile,” Thurmond said in an interview. The state Department of Education is now investigating a civil rights complaint against the district.

Less than a week later, the board fired the district’s popular superintendent, Jodi McClay, following the lead of new conservative school board majorities in Florida, South Carolina and nearby Orange County.

McClay’s supporters packed the high school auditorium and pleaded with the board to keep her on. When that failed, they drowned out a small group of the board’s supporters with a barrage of boos, continuing for hours.

In California, where the Republican Party has long been shut out of statewide office, GOP officials played a role in Temecula’s election as part of a broader strategy targeting low-turnout school board races. There’s also another advantage for outnumbered California Republicans: The party affiliations of school board candidates don’t appear on the ballot, as those races are technically nonpartisan.

Republican National Committee member Shawn Steel’s law firm donated to Thompson’s PAC, while Dobler, the county GOP chair, helped with candidate recruitment and funding in Temecula and elsewhere, an effort he described in an interview on Thompson’s YouTube channel.

Steel discussed the strategy at a March meeting of “The Parent Revolt,” a California GOP group that recruits and trains local candidates. “We make it look very nonpartisan, because every time you run for school board office, it’s nonpartisan,” Steel said. “And they’re the ones that people are least likely to vote on.”