Black-owned businesses to support in South L.A.

The shiny teal pickup truck that gleams in the parking lot at Earle’s on Crenshaw. The maze-like Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, where a cozy dessert shop and stylish restaurant hide behind multilevel parking garages. The 780-foot-long “Great Wall of Crenshaw” mural that depicts key points and figures throughout Black history.

These are just a few of the landmarks that color Crenshaw Boulevard, a 23-mile-long thoroughfare that stretches from the high-rises of Mid-Wilshire to the cliffsides of Rancho Palos Verdes. Zoom in on the sections bordering neighborhoods like Jefferson Park, West Adams, Leimert Park and View Park-Windsor Hills and you’ll find the pulse of Black Los Angeles.

“We have a high concentration of Black residents and businesses right along the boulevard,” says Jason Foster, president and chief operating officer of Destination Crenshaw. “We have cultural references from music to movies, and people who are actually driving the culture, like Issa Rae and Ava DuVernay, who got their grounding right here on Crenshaw.”

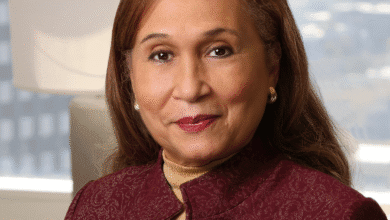

Duane Earle of Earle’s on Crenshaw.

(Mariah Tauger / Los Angeles Times)

The Crenshaw corridor has undergone drastic changes in recent years, including the sale of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza to a local developer and the creation of the Metro K line that runs at-grade from West Vernon Avenue in Leimert Park to Slauson Avenue in Hyde Park. As developers prepare for new tourists and residents coming to the area, additional mixed-use residential and retail developments have emerged.

Intent on reducing displacement, Destination Crenshaw aims to transform Black L.A.’s main thoroughfare with community investment, green spaces and public art commissioned from more than 100 Black artists. The years-long project is expected to be unveiled later this year, and Foster’s hope is for Crenshaw to live in public consciousness as “a Black place,” similar to Harlem’s 125th Street, which has been a center for Black arts and culture since the early 20th century.

“It’s so critical to see permanence as far as our culture and our businesses on this street,” Foster says.

Greg Dulan and his family have been titans in L.A.’s restaurant scene for more than 50 years, beginning with the fast-casual mini-chain Hamburger City founded by his father, Adolf Dulan, in 1977 and followed by Aunt Kizzy’s Back Porch, which became Marina del Rey’s first soul food restaurant when it opened in 1985. In 1992, just six weeks after the Rodney King riots, Greg Dulan opened his own restaurant, Dulan’s on Crenshaw.

To promote the opening, Greg did an interview with a local news channel, but when it aired the host mistakenly announced that the soul food spot — the first Black-owned restaurant to open on Crenshaw Boulevard since the riots — was giving away free food. Within minutes, Dulan’s on Crenshaw was swarmed.

“We had lines of people and sold out of everything,” says Greg. “That was probably the best marketing move.”

Just like Aunt Kizzy’s Back Porch, Dulan’s on Crenshaw quickly became a neighborhood fixture, even attracting celebrity clientele.

“Rosa Parks and Mayor Tom Bradley would come to the restaurant and eat breakfast,” Greg says. “But the main thing I love is the people of Los Angeles.”

The community support for Dulan’s on Crenshaw — recently reopened after a years-long renovation that added a second kitchen for catering and additional seating for dine-in customers — hasn’t waned. Days after the restaurant’s grand reopening, Greg gets emotional, saying, “I love what I do and I love where I do it. I love working in the neighborhood where I grew up. I feel like I’m making a difference, you know what I mean?”

Newly renovated, Dulan’s on Crenshaw stands out with bright green and red signage.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Other Black-owned restaurants nearby haven’t been as lucky. After three years of service, Hotville Chicken — a counter-service restaurant from Kim Prince, whose family is behind the original Nashville-style hot chicken recipe — closed in the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza in late 2022. In a city teeming with hot chicken outposts, the closure was a stark reminder of the additional hurdles faced by Black restaurant owners.

Greg Dulan, who is partnered with Prince on the Dulanville food truck, says he was motivated to remodel Dulan’s on Crenshaw in anticipation of the K Line bringing more visitors to the neighborhood.

“I did not want to have a dated restaurant trying to compete with brand new restaurants,” he says. Now, you can’t miss Dulan’s Christmas-themed signage on the corner of Westmount Avenue. On weekends, the new covered patio hums with post-church activity.

But don’t disregard the storefronts that aren’t as flashy. There’s plenty to discover along Crenshaw Boulevard, from murals honoring neighborhood rap icon Nipsey Hussle to the Taste of Soul festival that draws more than 350,000 attendees for a one-day celebration of Black food and culture. This guide serves as a primer for getting to know the Black-owned businesses in this district, including a long-standing barbecue joint, a community-minded cannabis club and much more.